Write what you know. We’ve heard this so often. But what does it mean? Does it mean that if I am a mechanic then I should only write about mechanics? Or if I am a woman, I can only write about women? No, of course not. What it means is that we should write what we know to be true, as opposed to what we wish were true, or hope to be true, or even what we believe to be true.

To “write what we know” means that we are being asked to write about something that we have experienced on an emotional level and come out the other side of. We have learned the lesson, and have been transformed by the experience.

In the story, Brokeback Mountain, Annie Proulx writes about a pair of twenty-year-old gay cowboys in Wyoming. Proulx is a seventy-year-old straight woman. But she wasn’t writing about cowboys, she was writing about the danger of not proclaiming your truth. She was writing about the universal challenge of standing up and being true to yourself in the face of possible resistance. She was writing about the tragedy that results when one is not willing to take the risk of loving. These are universal themes. In other words, we have all had the experience of being faced with a situation where doing something will put us in a position of receiving flak, and we must ask ourselves where our values lie.

There is a basic tension that underlies every human interchange. It is constantly at play. The tension between wanting to belong and wanting to be an individual reveals the constant struggle for an identity. It is a struggle that never ends. We are still struggling with it on our deathbeds. It is the struggle for authenticity. I submit that it is this struggle from which most, if not all, stories emerge. It is this struggle that begets the large thematic questions, such as, Who am I? Where do I belong? What is my purpose? What is love? We are constantly struggling between desire and fear. The desire to belong, and the fear of losing our identity or sense of purpose.

Story, like life, is a constant search for our true identity. As soon as we think we’ve found the answer, another problem arises that distracts us from the truth. The truth is that we are OK right now, in this moment. It is important, as storytellers, to understand this basic truth. When we are connected to the truth that our protagonist is already free, we are, paradoxically, far more inclined to put them in harm’s way, to explore their conflict.

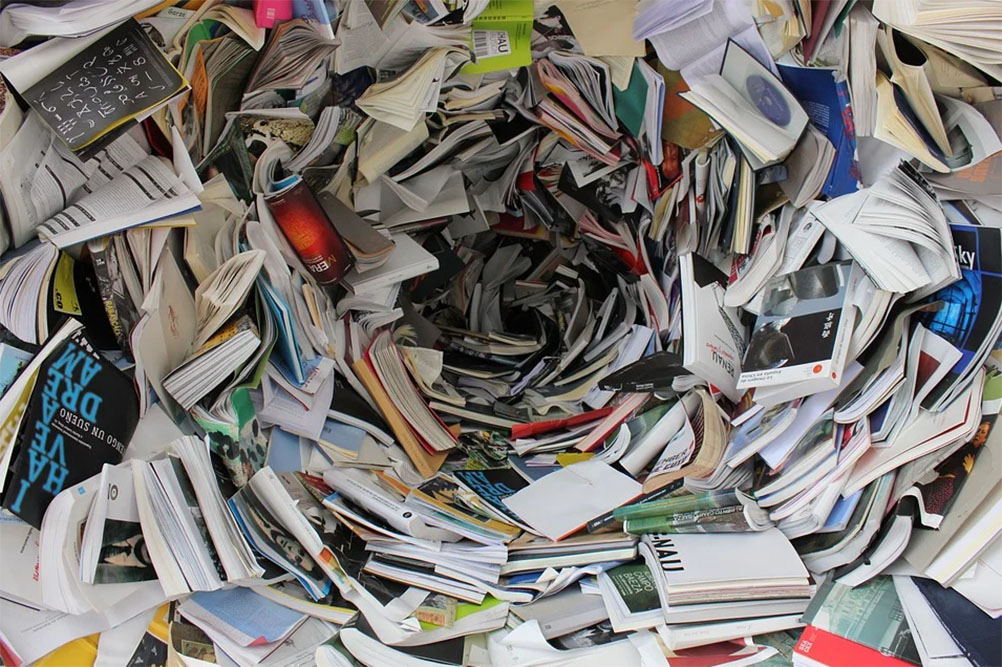

The challenge in writing what we know is to hold the images and ideas that we write down loosely. Sometimes the first image or idea that we write down is in fact a gateway to a deeper or more specific idea or image, the real place the story wants to go. If we hold on tightly to the first image, we will never allow our unconscious to go where it really wants to go. Ideas can be like weigh stations. We submerge to a level, and we swim around in it for a while, and then we get comfortable there, and we go deeper.

Our unconscious does not push us into areas that we are not equipped to handle. Because of this, it takes time to become comfortable with new consciousness. Story is about this shift in consciousness. What happens (plot), is merely a vehicle to illuminate the beats that lead to this transformation.

Let me repeat. Hold your ideas loosely. Do not become too attached to what “must” happen. We are always moving from the general to the specific. If you hold onto an idea too tightly, you will become blocked and choke off the possibility of the real truth from emerging.

Do you have a theme that you consistently return to?

Learn more about marrying the wildness of your imagination to the rigor of structure in The 90-Day Novel, The 90-Day Memoir, or The 90-Day Screenplay workshops.

Writing Prose

Writing Prose